The book Visual Language for Design: Principles for Creating Graphics that People Understand by Connie Malamed does a great job of explaining basics of visual design and putting them into the best context for learning professionals and is highly recommended. This will allow you to use shape, color, and other aspects of visual design to draw the learner’s attention. While creating visual components of your training materials, keep the basics of good visual design in mind (or hire someone who knows them).Our brains are very attracted to visual stimuli, so try to include lots of visual input in your training materials.If possible, use a training room that’s removed from the work area.

Sensory memory free#

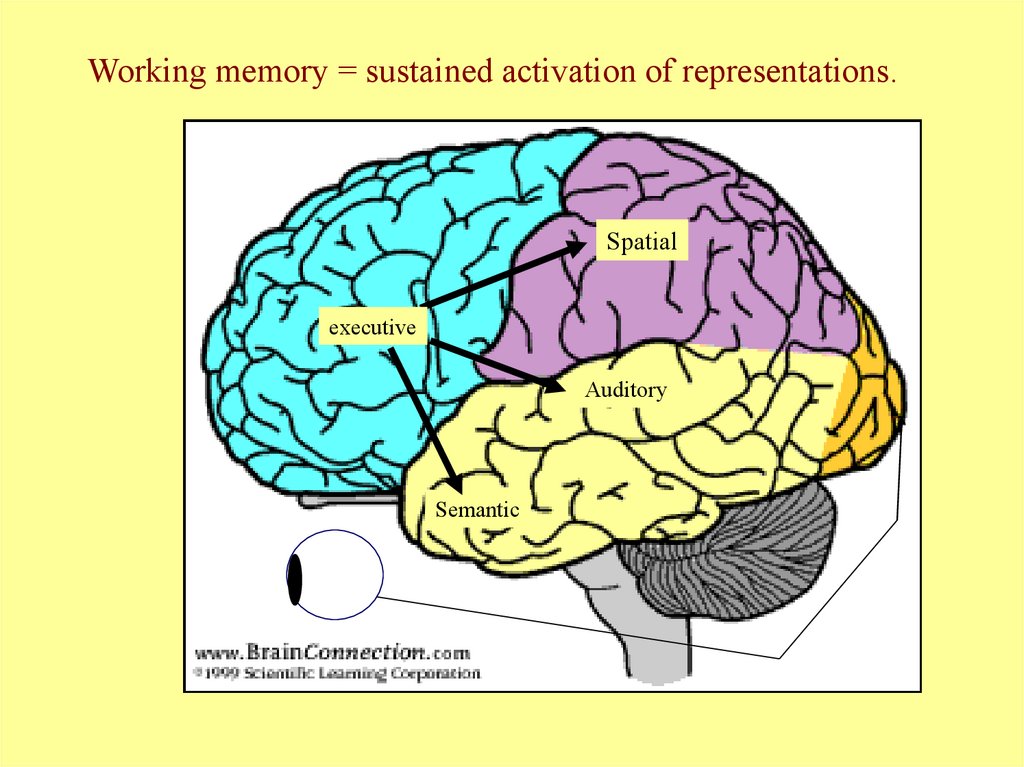

Instead, our brain plays an active (if often subconscious) role in selecting the information that it will pay closer attention to. The information that passes from our sensory memory to our working memory doesn’t get there by chance. And, you want outside distractions and distractions created by chaotic training materials to NOT enter the working memory. You want specific sensory information to get into the working memory: the content you’re covering in training.

And it’s why if you’re trying to help employees learn, you want to try to draw their attention to the right stuff to get past that bottleneck.Ĭonvergence Training are workforce training experts.Ĭlick the links below to learn more about how we can help you.ĭownload our FREE Guide to Writing Learning ObjectivesĪs a learning professional, if you want people to learn from your training materials and later apply that learning on their job, this is your first hurdle: getting sensory information through the sensory memory and into the working memory.īut it’s more than just that. This is why people sometimes say that the working memory is a “bottleneck” within the learning process. The rest of that information is essentially lost. Some of that information goes on to be processed by our working memory this is when we become aware of the information. The information stays in our sensory information for a very short time-in many cases, only a fraction of a second, though in some cases, it may last for a few seconds. In this post, we’ll look at the transition from Step 1, “We experience information through our senses and sensory memory,” to Step 2, “Some of that information is processed by our working memory.”Īs we learned earlier, in Step 1 sensory information (sights, sounds, etc.) is perceived by our sense organs (eyes, ears, etc.) and is briefly processed by our sensory memory. In a recent blog post titled “ The Human Information Processing System: How People Learn (or Don’t),” we went over five key steps in which people learn and later apply information.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)